Setting the record straight: Reconceptualization of the Ukrainian Revolution

The Ukrainian revolution lost an armed struggle, since people were not ready to accept the idea of independence. The nation with no secondary and higher education of its own is doomed to failure. Revolution does not prevail in countries, were rural residents constitute the greater part of socially active population.

There are several fundamental issues dominating the interpretation of our national struggle for independence. We will provide short review to clear out major issues that might hinder the understanding of Ukrainian Revolution of 1917—1921.

When did the Revolution start and how long did it last?

There are several approaches to establishing timespan for the revolution: narrow and broad. Those historians who tend to view the Ukrainian Revolution in global context associate its start with the WWI, which expedited the fall of empires and triggered social and national revolutions almost in all the East European countries.

|

|

Ukrainian rally at St. Sophia Square in Kyiv, March 1 (19), 1917 |

The end of struggle for independence is associated with finalization of the Paris Peace Conference and subsequent interstate agreements, which sealed the fate of the Western Ukraine by assigning it to the Commonwealth of Poland. In this all-European scenario of global map shifts, the dates for Ukrainian revolution would be set at 1914—1923.

This timeframe looks reasonable, as with the beginning of the WWI political circles of Western Ukraine put the issue of gaining Ukrainian independence on their agenda.

This objective was supported by the Head Ukrainian Council (GUR) in Lviv; this cause also became the Sich Riflemen’s mission.

When it comes to revolutionary events on the Ukrainian territories that used to be under the rule of Russia, they started with March events in Kyiv, and ended with the Peace of Riga of 1921 — treaty between the Bolshevik Russia and Poland, that distributed Ukrainian territories between occupying Poland and RSFSR.

There is another time-line that sets the events at 1917—1920, which coincides with Russian Communist’s dates for the so called civil war. It describes Ukrainian events inside the context of Russian history. We consider both approaches feasible, with time-line set at both 1914—1923, and 1917—1921.

However, it is not entirely reasonable to consider years of 1921—1923 to be the end of the Ukrainian Revolution. Anti-Bolshevik uprisings continued to occur in villages up until mid-1920s.

The existence of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC), Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, cooperative publishing movement, peasant land ownership, and other public organizations and structures that carried on the traditions of independent Ukraine indicated of the revolutionary achievements being maintained for at least another decade after the end of Ukrainian Revolution.

Among those achievements, the Ukrainization of 1920-s and the "executed" cultural renaissance, mainly in literature, should also be mentioned.

The real end to the Ukrainian revolution came with the trial of the Union for Liberation of Ukraine, mass collectivization, and repressions against intellectual elite and, finally, the Golodomor of 1932-1933.

Thee simultaneous revolutions within the same time frame and on the same territory

Talking about the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917—1921 we often associate our land only with the struggle for independence. However, there were actually three revolutions happening simultaneously on this territory:

The first one was Russian Democratic Revolution. It had its own revolutionary authorities — the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, the governorate commissars who answered to the Provisional Government, armed forces of the former Imperial Russian Army, that were oriented towards "one and indivisible" Russia.

Its objective was to establish liberal Russian republic with possible federation of some of the territories, including Ukraine

.

It extended to, and was followed by, the Russian totalitarian leftist revolution lead by the Bolsheviks that had their own Red Army military forces, and party cells — germs of the future Communist state. When it came to national policy issues, they, first, adopted center-oriented position, but later conceded to status of Ukrainian as a federal state.

The second process — international revolutions of Poles, Romanians, Hungarians, who were planning on expanding their own national revolutions from their title land and into Ukrainian territories.

|

|

Polish workers rally in Luhansk. May 1, 1917 |

Each of them aspired to include ethnic Ukrainian territories in their own country of Great Poland, Romania, or Hungary. As a result of military actions of Hungarian, Polish, Romanian armed forces, territories of Galicia, Western Volhynia, Transcarpathia, Bukovina and Bessarabia were separated from Ukraine.

Revolutionary activity of the Jewish community also needs to be mentioned. The latter sided with the Polish cultural majority in Galicia, and supported rather the Russian Bolsheviks in Dnieper Ukraine.

And, finally, the third was the Ukrainian Revolution. The Ukrainian revolutionary forces intended to turn Ukraine into a subject of international law, and establish an independent state.

|

|

Announcement of the III Universal of the Central Rada of Ukraine at St. Sophia Square in Kyiv. In the center — Symon Petliura, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Volodymyr Vynnychenko. November 7 (20), 1917. |

The Ukrainian forces were combined of leftist and left-centrist parties — USRDP (Social Democrats), Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party, and Ukrainian Socialist-Federalist Party, and a small fraction of UPSS (Socialist-Independists).

They formed the Central Rada and aspired to get a constitutional "divorce" from Russia: first as an autonomy/federal state, and later as independent state.

The Ukrainian Revolution in itself had two constituents. The republican version of the UNR state development was more popular. The conservative, Germany-oriented movement, trying to establish the Ukrainian State was of lesser power.

The third component to revolutionary movement were the attempts of Western Ukrainians at building independent state — establishment of the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR) as centrist state based on ideology of the National Democratic Party.

Another process, taking place in the same time as the three revolutions, was anarchist (with weak national position) movement and operation of multiple rebel warlords. Some of those were building Ukrainian state in a single region (warlords Zeleny, Chuchupaka, Struk and others), or an anarchist quasi-state (Bat’ko ("Father") Makhno in the South East of Ukraine).

During the revolutionary events all the major players in Ukraine were in the state of constant war with each other. Each tried to build its own national state on some or other territory. This caused permanent wars that lasted through all of the period: Russian-Ukrainian and Polish-Ukrainian.

Counties of the East-Central Europe avoided this type of wars, since by 1917 there already existed organic mono-ethnic cultural and public communities, which formed a new type of political Pole, Czech, Fin.

Inter-state war, not a civil war

It is a huge mistake to call Ukrainian struggle for independence a "Civil War".

Using the term "civil war" means that the talker does not acknowledge the existence of the UNR — the Ukrainian State.

Instead, in that period, we deal with inter-state wars that should be classified based on sides of military conflict: Ukrainian-Russian (Volunteer Army also known as the White Army), Ukrainian-Russian (Bolshevik) wars, and Polish-Ukrainian wars in Galicia and Volhynia.

The term "civil war" was polarized by Russian Communist historiography and propaganda, which tried to avoid noticing the UNR existence, and, correspondingly, presented the Red Army’s occupational activities in Ukraine as legitimate.

Despite the UNR defeat in Ukraine’s war against Bolsheviks, we should speak of occupation of the Ukrainian land by the Red Russia.

Consequently, the puppet government of the UkrSSR did not represent interests of the Ukrainian nation, and was in fact a collaborator government. The condition of Ukraine upon its final capture in 1920—1921 by Bolshevik Russia corresponds to that of a colony.

The establishment of quasi-state of UkrSSR appears as positive in comparison to pre-revolution Russian Empire, when Ukraine under Russian rule was divided into 9 governorates. Tsarist Russia did not recognize the existence of Ukrainian nation; Bolshevik Russia de facto recognized the existence of Ukrainians, but only as loyal servants to Moscow.

Two terms were introduced: a Soviet Ukrainian and a Ukrainian Bourgeois Nationalist. This corresponded to pre-revolutionary terms: Maloross [Little Russian — edit. note], and conscious, or true, Ukrainian.

From the very start, the Russian occupier introduced double meaning to the very notion of being "Ukrainian", this continued the old Russian chauvinistic tradition of treating Ukrainians as a brunch of "triad Russian people".

Rada or Soviet?

International historiography and public and political thought used the term "Soviet" to identify the essence of the state system in Ukraine after 1921.

This clearly identifies Russian occupational regime that ruled in Ukraine after the defeat of the UNR Directory.

This was an attempt to differentiate between the authentic Ukrainian national institutions and the colonial ones, brought about by the Red Army.

This was about right, since international practice does not translate the names of authentic foreign state structures and institutions: it’s KGB, not a CSS, and NKVD, not a PCIS, etc. The term "radiansky" following this pattern was translated as "soviet"; meanwhile in Ukraine they used word "radiansky" to mask Communist totalitarianism as power of the people — or "Rada" — that authentically means "people’s council".

Ukrainian historians keep using the term "radiansky" to describe the state system brought about by Bolsheviks. However, there were no "radiansky" state authorities a priori.

|

Rada (council) based form of state power vanished with the crackdown of the Russian Constituent Assembly.

By using the term "radiansky" we add to further confusion, since it was the Central Rada that might deserve this definition, since it was really a form of government based on people’s council — Rada. Meanwhile, "Soviets of People’s Deputies" were nothing like that.

The Central Rada included all the socialist parties, and not just Ukrainian, but also Russian, Polish and Jewish. It had never received full-fledged national legitimization through national elections, due to the advance of Bolsheviks troops. Also the rightist forces were denied representation.

If we consider the dictatorship of the proletariat as totalitarian despotic form of power of a single party, such idiomatic expression as "radiansky regime" renders no meaning whatsoever. Since "radiansky", or rada-based, government cannot be totalitarian.

Should we consider collaborators those Ukrainians who supported the Bolshevik Russia?

Up until now in Ukraine the term "collaboration" is only used with regards to Ukrainians who worked with the German occupation regime of 1941—1945.

However collaboration started much earlier, when huge number of Ukrainians supported the Russian Bolshevik occupation army in 1918-1920-s. This collaboration had two major forms:

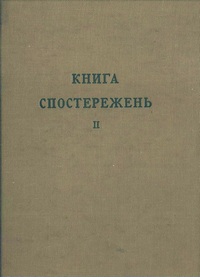

The first one was collaboration aimed at establishing a leftist (communist) independent state in Ukraine. This type of collaboration, taking every circumstance into account, might be considered the lesser evil. Among those were Ukrainian Bototbists and Ukapists (members of the Ukrainian left nationalist and communist parties), as well as RKP (b) members, who were conscious Ukrainians: V. Ellan-Blakytny, M. Skrypnyk, O. Shumsky, P. Liubchenko, M. Khvyliovy, A. Richytsky, and others.

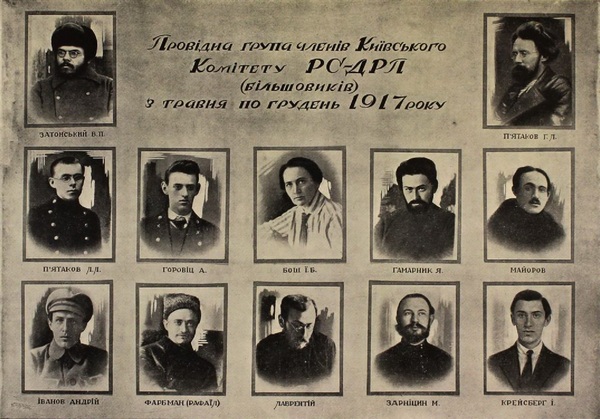

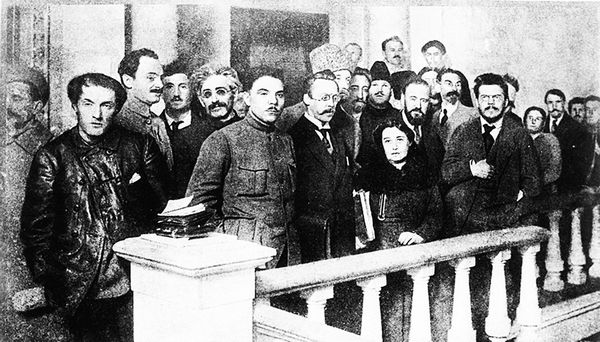

|

|

Leaders of the KP(b)U during the war of Ukraine against the Bolsheviks. Left to right: Oleksandr Khmelnytsky, Moissei Rukhymovych, Moissei Granovsky, Volodymyr Yudovsky, Kliment Voroshilov, Volodymyr Meshcheriakov, Mykola Podvoisky, Anzhelika Balabanova, Christian Rakovsky, Mykola Skrypnyk, Volodymyr Zatonsky Photo: Wiki |

Effectively, this cannot be considered collaboration, since these activists truly believed they were building independent Ukraine.

The second form was a willful collaboration with occupational army as ones’ ideological ally. The latter was of mass scale; for the most part it involved nonpartisan people who kept thinking inside the frame of "one and indivisible" Russia.

Struggle against Russian national idea, the "Russki mir"

The Ukrainian Revolution of 1917—1921 not only gave life to a modern Ukrainian. In its wider sense it became a stumbling block to the spread of Russian national idea beyond the borders of former Russian Empire.

The attempt at establishing a state structure in ethnic Ukrainian territories — which were almost twice as large as modern Ukraine — forced Russians to give up on their idea of annexing Bosporus and Dardanelles with Istanbul to their empire to ensure domination in the Balkans.

The Ukrainian Army and rebel troops had stopped the Red Army from proceeding to Europe in 1919—1920.

Ukrainian idea revived Kuban, Ukrainian population of Voronezh and Starodub, the Ukrainians of the Far East, who even tried to establish the Far East Ukrainian republic, and even China, where in Harbin operated powerful cultural Ukrainian institutions.

Kuban Cossacks fought in the UNR armed forces, secondary and higher Ukrainian establishments were open in Yekaterinograd and other stanitsas; one of the best poets of the "Executed Renaissance" Yevgen Pluzhnyk was from Voronezh region.

Rostov-on-Don was a part of ethnic Ukraine, as well as Taganrog, and Land of Berestia [modern Brest in Belarus — edit. note].

However, the epoch of de-Ukrainization and ferocious advance of Russian chauvinism in 1920—1930-s liquidated Ukrainian national resistance inside the Russian state.

Autonomy, federation, independence: did they contradict each other or were they mere sequence of events?

Former Hetman supporters and conservatives argued that they had an exclusive right to talk about the Ukrainian Statehood, and refused this right to republicans (UNR supporters), calling them federalists, unable to grasp the idea of independence.

Vyacheslav Lypynsky did a lot to that end. Talented speaker, he was seeking allies in a "hostile camp".

However, unwittingly, he convinced the opponents that all of the UNR followers were federalists. And that was why independence struggle had failed, since, they said, the leaders of revolution — M. Hrushevsky, S. Petliura and V. Vynnychenko — were arch enemies of their own state.

|

|

M. Hrushevsky, S. Petliura and V. Vynnychenko in November of 1917 |

In their turn, republicans (M. Slavynsky, P. Chyzhevsky, P. Khrystiuk) emphasized the non-Ukrainian character of Hetman’s State. They called it a Maloruss construct, that, de facto, created a territory allied to Russia.

In fact, M. Hrushevsky was the person who mentored most of the Ukrainian conservatives (S. Tomashivsky, I. Krevetsky, to some extent — V. Lypynsky were his students).

To Ukraine federalism was a disease of statelessness, weakness of its public life. This weakness pushed leaders of the Ukrainian movement towards seeking compromise with overpowering Russian influence in Ukraine.

Autonomy/federation was a compromise with the Russian national idea, but not a denial of Ukrainian statehood.

M. Hrushevsky, as well as the Socialist-Federalist Party, perceived federalism as the first step to independence.

M. Hrushevsky wrote that federation is the next step upon independence, as he was envisioning future establishment of the European Union.

Frustration of defeat should not divert us from the fact that both leftist and rightist forces were doing the same job; they used different tactical means, but they did have a common objective.

Different projects of Ukrainian statehood

There is a trend among historians who favor the UNR or the Hetman, to contrast their team against the opponent, as more reasonable or better.

In their discussions, the opponents accuse each other of supporting the views of enemies of the Ukrainian statehood. Say, according to Hetman supporters, the Borotbists betrayed the idea of Ukrainian independence when they collaborated with the Bolsheviks, leveling themselves with the occupier.

The other side, in their turn, accuses Ukrainian nobility of betraying the Ukrainian national idea by siding with the Hetmanat, and, thus, acting in the interests of alien Russian monarchist idea.

When interpreting the Ukrainian Revolution it is important to understand that both state forms were viable in Ukraine: republican or conservative. Had any of them succeed, Ukraine would equally win. That’s how this matter was viewed by real patriots.

|

|

Dmytro Doroshenko |

For instance, Dmytro Doroshenko was a member of the UNR General Secretariat, and in the times of the Ukrainian State, acted as the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Fedir Lyzogub’s Cabinet. Vyacheslav Lypynsky, upon Hetman’s overthrow, remained the Ambassador of the UNR Directory to Vienna for half a year. Oleksandr Lototsky was both a member of the Central Rada and the Minister of Religious Affairs of the Ukrainian State.

Ivan Ogienko was Rector of Kamjanets University during P. Skoroparsky, and acted as the Minister of Religious Affairs in the UNR Directory Government.

In the first months of revolution S. Petliura and even V. Vynnychenko were seeking common ground with Skoropadsky.

Number of senior officers served at both armies - the UNR and the Ukrainian State.

Yevhen Chykalenko was very upset with demise of P. Skoropadsky’s state due to the UNR Directory uprising. He thought it was better to have half-Ukrainian state with pro-Russian Government, that to get Russian statehood in form of Soviet Ukraine.

Half-Ukrainian state in time might turn Ukrainian. There is no such possibility for the Russian state.

Did Skoropadsky’s Ukrainian State have political thrust towards independence?

Some historians wrongly ascribe P. Skoropadsky strategic orientation towards independence of the period of his cooperation with USKhD (Ukrainian Union of State Farmers) to the period of May-November 1918, when Hetman was clearly under the influence of Russian imperialist ideology and was a political Russian. P. Skoropadsky’s "Spogady" memoirs reveal his Russian cultural and statehood priorities; due to the pro-Russian nature of the memoirs V. Lypynsky refused to publish the complete version of memoirs in "Khliborobska Ukrajina" printed edition.

Of course, the Ukrainian State of P. Skoropadsky had some grave achievements in the field of development of the national culture (Ukrainian Universities in Kyiv, Kamjanets, Poltava, gymnasiums, the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, theaters, museums, etc.). It also made good progress in the international arena (acknowledgement of Ukrainian independence by number of European states).

However, according to P. Skoropadsky himself, his dream was a federal Russia, with Ukraine as a part of Russian political space.

|

|

Kaiser Wilhelm II and Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky |

It was German Kaizer, who pushed Hetman towards the idea of independence, as the German Empire wished to see Ukraine as its ally that had broken off all relations with Russia.

It was due to Skoropadsky’s Moscow-filia that the notorious federation decree was issued; it also became the trigger to the Directory uprising.

P. Skoropadsky relied not on the Agrarian Democratic Party of V. Lypynsky, D. Dontsov, M. Mikhnovsky and V. and S. Shemet brothers. This would have been totally logical had Hetman wished for truly independence-orientated state.

Instead, Hetman rather relied on the pro-Russian Protofis and Landowner Union (SZV). The latter represented forces of Russian capital and squireship – they consisted of former activists of imperialist, monarchist and blackhundredist parties.

Skoropadsky considered both Lypynsky and Dontsov, and even D. Doroshenko, way too far-Ukrainian, even chauvinist.

To Hetman, the exemplary Ukrainian would be such a figure as V. Naumenko, or M. Vasylenko who adopted "Maloross" believes.

Hetman attempted to balance keeping it neutral with both UKhDP and Protofis. However, due to prevalence of pro-Russian political forces, he turned into a representative of their political interests.

P. Skoropadsky became a Ukrainian politician after he was forced to immigration. This happened mainly under V. Lypynsky’s influence.

Who is more of a statesman – Hrushevsky or Skoropadsky?

Historians who favor P. Skoropadsky often present Hetman as more of a statesman, and a better one, than a National Democrat M. Hrushevsky.

They argue that Hetman was an experienced landowner and had a better grasp of building a state, than intelligentsia representative Professor Mykhailo Hrushevsky.

|

|

Professor Mykhailo Hrushevsky, the Head of the Central Rada |

The source of such contemplations is in the "Lysty do brativ-khliborobiv" ("Letters to brethren-agrarians") by V. Lypynsky: conservatism is better than anarchy prone republicanism.

However, theoretic assumption is one thing, while the reality of Skoropadsky’s Ukrainian State has already proven to be totally different.

In 1918, P. Skoropadsky was not a Ukrainian statesman, in Ukraine he attempted to preserve political system of the late Russian Empire; in this he relied on Russian cultural circles of squireship and entrepreneurs, who were natural enemies of conscious Ukrainians.

P. Skoropadsky did not acknowledge traditional postulates of Ukrainian policies of mid-19th century: such notions as "ethnic Ukrainian territories", "Galician Piedmont", common cultural tradition of both Ukraine - under Polish jurisdiction, and under Russian one. Skoropadsky did not know Ukrainian literary language; he considered its version of the time to be "creation of Galicia".

Despite some break from war actions, Skoropadsky was unable to conduct agrarian reform, which would grant him support of wealthy farmers.

He could not come to a compromise with non-radical socialists.

Hetman was oriented towards the White Russia, and de facto was an ally of A. Denikin who with regards to national issue had strong reputation of "butcher of Ukrainians".

|

|

Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky |

Hetman also was in opposition to Galicia, and had no intention of using its state-building potential; he blindly believed in the importance of Russian culture for Ukraine.

On the other hand, M. Hrushevsky, ever since late 19th century, fought for autonomy of Ukraine in both empires: Russian and Austrian. Basically, he was the one who prepared Ukraine for perceiving the postulates of independence.

Hrushevsky continued the legacy of Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius secret society, which, while focusing on the idea of Ukraine’s federal future, had never discarded the idea of its independence (T. Shevchenko, P. Kulish).

Using "New age" and "Galicia as Ukrainian Piedmont" policies M. Hrushevsky created informal Academy of Sciences (NTSh) in Galicia.

He trained the new intelligentsia who set the issue of national authenticity in focus of their public activities.

In his book "On the Threshold of the New Ukraine" (March 1918) Hrushevsky professed the need for Ukrainian independence, importance of building an independent state and terminate Moscow orientation.

Hrushevsky is one of the fathers of the ІV Universal of the Central Rada, and initiator of March 1918 treaty with Germany.

In both his actions and words Hrushevsky was more of a supporter of Ukrainian independence, then federalist Pavlo Skoropadsky – at least, when it comes to Hrushevsky and Skoropadsky of 1918.

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk of 1918. Should the Germans be called occupiers?

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a huge victory for Ukrainian diplomacy, having pushed Ukraine to international arena. The UNR acted as opponent to the Entente, but in turned from a subject of historic process, into an object.

The peace treaty helped deal with the Bolshevik anarchy that engulfed Kyiv, and return Central Rada back to power.

|

|

Meeting of German, Ukrainian and Russian delegations in Brest-Litovsk |

Under the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Ukraine received the largest territory in the history of the State – it included all of ethnic Ukrainian Berestia, Gomel and Mozer regions (modern Belarus); part of Don – the cities of Rostov-on-Don and Taganrog (modern Russia).

According to the secret part of the treaty, Germany and Austria-Hungary recognized the Western boarder of Ukraine set at ethnic territories – along the San River and the Bug River (Peremyshl was supposed to be Ukrainian), and they also agreed on splitting Galicia into two Crown dependencies: Ukrainian and Polish.

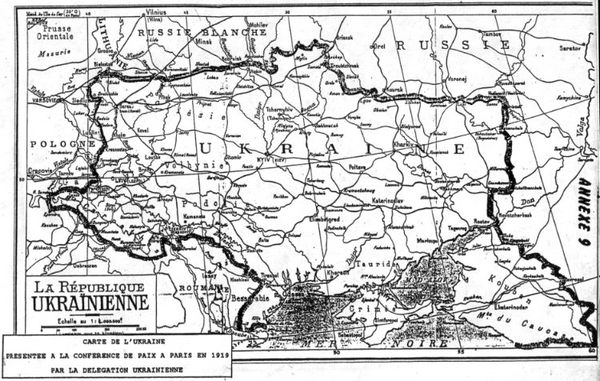

|

|

Map of the Ukrainian Republic presented by Ukrainian delegation at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 |

Brest-Litovsk events resolved the psychological problem of Ukrainian politicians, who used to look at international policy with the Russian state interest in mind. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk ended the so called "canine obligation to Moscow" (M. Hrushevsky).

However, this creates a new issue: should German troops be considered (according to established tradition of Communist propaganda) occupying forces?

Bolshevik troops, who fought against the UNR, were definitely an occupier. The German Army came to Ukraine as the UNR allied forces. German officers did abuse their position as allies practicing repression against certain forces. However, there is no legal evidence to support the idea of German army being an occupier.

If we compare activity of the Bolshevik army red units in Ukraine, with the activity of German military units, the result will not be in favor of Russian Bolsheviks. German army took grain within limits - in amounts agreed upon with the UNR. This comparison reflects occupying nature of the Communist regime in Ukraine.

Bolshevism as Russian phenomenon. Difference between Ukrainian leftist movement and Russian Communism

Nikolai Berdyaev once wrote that Bolshevism is a purely Russian phenomenon. Independent of Berdyaev, similar thought was expressed by Yevhen Malaniuk.

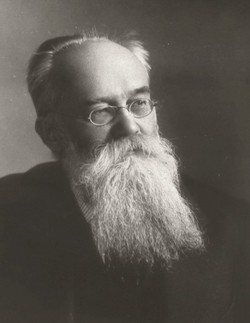

|

|

Nikolai Berdyaev "The Origin of Russian Communism" |

So, is there any reason to talk about Ukrainian Bolshevism of the times of the Ukrainian revolution?

Definitely, there was a certain share of Bolsheviks of Ukrainian descent in the RCP (b).

However, Bolshevism was exported to Ukraine from the North.

In Ukraine, Bolshevik Party was formed with Russian, or de-nationalized element – residents of proletarian cities.

In Ukrainian cities with no significant manufacturing, among the members of other revolutionary parties Bolsheviks never exceeded 10-15 %.

Without Russian weapons, local Bolsheviks would have never come to power in Ukraine.

|

Also, leftist parties in Ukraine didn’t have openly Bolshevik views.

Neither Ukapists, nor Borotbists, who created Ukrainian national Communism had none of Bolsheviks’ rigidity or extreme radicalism.

They were ready to tolerate private ownership, were not opposed to multiculturalism, had more democratic views and leaned toward parliamentarism.

Most of members of these parties who later became Communist were compelled to do so by the force of circumstance.

With the end of Ukrainization, former members of these parties were the first to suffer repression, became objects of exemplary trials, turned out on execution lists, or committed suicide.

Russian Communist regime did not believe in good intentions of Ukrainian Communists, suspecting them of nationalistic views.

The class transcendence of the Ukrainian socialism

Ukrainian socialism attempted to define its place in between social and national set of priorities. National priorities prevailed in the times of the Ukrainian Revolution.

Building national state became the most critical issue, obtaining social benefits for the working class was of secondary importance, which depended on the ability to solve the national issue.

Ukrainian EsDecs were not as much of worker descent, but rather intelligentsia of rural origin. S. Petliura was of Cossack and clerical background, O. Skoropys-Yoltukhovsky and M. Melenevsky – were representatives of the Right Bank nobility, Valentyn Sadivsky was from a priest family, and Levko Yurkevych belonged to nobility, while Andriy Zhuk and Volodymyr Doroshenko were of peasant-Cossack descent.

According to their social attitudes, Ukrainian EsDecs were close to Russian Mensheviks. Only Levko Yurkevych and Mykola Porsh were of orthodox views.

During the UNR Directory, the EsDecs sided with the right-centrists forces – socialist-federalists, who, when it came to social issues, were not really socialists. In modern terms, they were rather a national party representing interests of intelligentsia and petty bourgeoisie.

Had they been seeking for an ally on social issues, it would be logical for EsDecs to side with the SRs. However, that didn’t happen.

Already in 1909-1912, the need for one-class approach was being discussed among USDRP members. The idea was to transform the party from the representative of interests of proletariat into an organ that would express the will of larger spectrum of forces – leftist to centrist – and turn it into the engine of national independence movement.

This was the position of the future members of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU) – A. Zhuk, V. Doroshenko, O. Nazariyiv, V. Stepankivsky. During the Ukrainian Revolution the USDRP did become such an engine - center of attraction to all party groups – leftist to national democrats – who’s platforms were based on idea of national independence.

Unfortunately, the Ukrainian socialism – unlike German, French, Austrian, or even Russian socialism – did not develop its own national theory.

There were no people like K. Kautky or P.-J. Proudhon in Ukraine, and ideological postulates were blatantly borrowed from Russian social-democratic theory and practice (Mensheviks and Bolsheviks).

Ukrainian socialists shared wrongful idea of common Russian-Ukrainian revolutionary front, which manifested itself in subordination of Ukrainian revolutionary movement to Russian revolutionary realia.

Difference in revolutionary strategy and practice in the Western and Eastern Ukraine

Longin Tsegelsky – the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR) in his memoirs describes difference in mentality of Western and Eastern Ukrainians.

When ZUNR officials arrived to some province in Galicia they were welcomed by already formed local government. On district level, people did not wait for an order from central authorities – Ukrainian communities already had their elected officials, local commissioners, judges, and public educators.

|

|

Postage stamp of ZUNR, May 1919 |

In cultural sense, Western Ukrainian had been ready for the state of their own: with powerful intelligentsia, "Prosvita" network, national Greek-Catholic Church, own cooperatives and banks.

On the territory of Ukraine formally controlled by Russia, in Volhynia, the train, carrying ZUNR delegation on its trip to Kyiv, was stopped by armed military unit of Otaman Bozhko, who ruled his territory as uncontrolled military leader.

Further East, Ukrainians were not building modern forms of authority – they were rather recreating archaic and, sometimes, even anarchic forms of old-times Cossack governance.

Galician Ukrainians, influenced by Austrian tradition and inspired by the example of the Poles, were building modern national society in the spirit of parleamentarism and tolerance to individuality.

In Dnieper Ukraine the countryside turned to Cossack tradition, and acted in accordance with the habitual practice of their community - in complete autonomy from the rest of Ukraine, oblivious to national issues.

Galician society was not just European, it was bourgeois.

The major National Democratic Party had no socialist elements; it wished to build an open and wealthy society in Ukraine. It aspired to bring the Ukrainian people up to the standards of Austrian and Polish society.

The greater Ukraine was captured by socialist doctrine. All of the parties were scared to look non-socialist, even if, in fact, they shared no socialist views.

The word "socialist" was attached to the name of the centrist UPSF (socialist-federalist) party, as well as to the UPSS (socialist-independists).

Socialism (and communism, which, at the time, was perceived as component of socialism) was the only thing to justify the existence of the Central Rada in a future State of Ukraine.

In the field of proprietorship, Ukrainian parties attempted to copy the ideas of Russian Bolshevism, followed its steps, despite being in their hart more of Euro-socialists, like J. Pilsudki’s PPS or K. Kautsky’s German Social Democrats.

Is unification of Ukraine all that really matters?

The idea of unification allowed establishing policy of "Galician Piedmont", turning Western Ukraine into a lab of a kind, all-Ukrainian cultural incubator.

It was the notion of unification, which turned Galicia into center of intellectual thought for both under-Russia and under-Poland Ukrainians.

In times of struggle for independence of 1917-1921 unification became the statehood cornerstone – the concept of unified UNR and ZUNR.

However, in times of defeat, it, according to some political thinkers, impeded the establishment of even a limited Ukrainian State at any of the ethnic Ukrainian territories.

In theory, the State of Western Ukraine might have established itself (though without Lviv) on the territory of Stanislaviv and Ternopil regions.

The principle of self-determination, laid down in Woodrow Wilson’s "Fourteen Points", maintained the right of peoples on the territory of former Austro-Hungarian Empire to their own statehood. Formally, this included Ukrainians. No such right was acknowledged for nations of former Russian Empire.

Representatives of the Entente at the Ukrainian Galician Army (UGA) headquarters made repeted suggestions of "limited statehood", however ZUNR leadership insisted on strict adherence to unification principles.

Andriy Zhuk voiced the opinion of political immigrants from Dnieper Ukraine to Galicia, when he wrote to S. Petliura, that instead of the Eastern Ukraine they should appoint Western Ukraine the center of Ukrainian statehood; that Ukrainian military forces and material resources should be concentrated in the better prepared for national independence Galicia, instead of the Dnieper Ukraine.

However, it happened the other way around: the UGA tried to protect East Ukrainian statehood, surrendering Eastern Galicia to occupation by Poland.

Meanwhile, only separate western and central territories of the Greater Ukraine were comfortable with the idea of independent state.

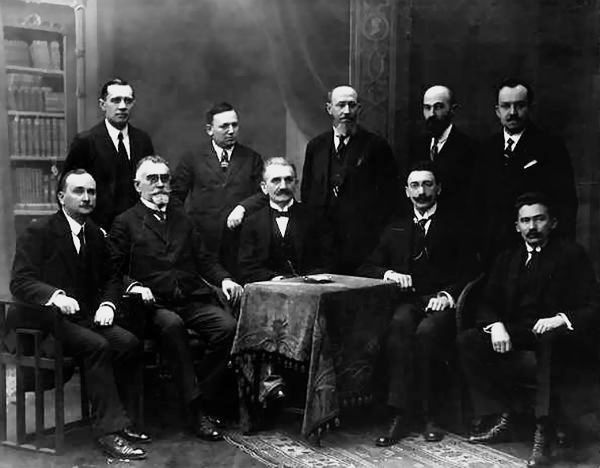

|

|

Government-in-exile of Yevgen Petrushevych – Dictator’s Board of Commissioners in Vienna |

Instead of conclusions

The Ukrainian Revolution lost its armed struggle, since the society was not ready for independence. Before the start of revolution, the Ukrainian society did not have enough time to complete cultural conquest, or to cleanse spiritual influence of, first and foremost, Russian cultural and national idea.

The nation with no secondary and higher education of its own is doomed to failure. All the other countries of the Central Eastern Europe had each their own national school. Some – had never lost its school, others started to re-establish it in the mid-19th century. Several generations had already been brought up by own national educators, meaning they were indoctrinated with national idea.

|

|

The building of the Pedagogic Museum, where the Central Rada of Ukraine conducted sessions. Photo of 1913

|

Revolution does not prevail in countries, were farmers constitute the greater part of socially active population. Only when the struggle is won in the cities, when cities become the flagship of strive for independence - only then one might speak of conclusive victory.

In Ukraine, there was not a single Ukrainian city. Ukrainians constituted around 15% of total population even in capital centers, such as Kyiv and Lviv.

Independence war in Ukraine was shaped as a war of uncoordinated, yet nationally aware, village against Russia-oriented city.

In Western Ukraine, Lviv was culturally Polish, and Polish urban population won itself a special national position.

Nation is unable to win a fight for its statehood, if its intelligentsia constitutes less than 10% of total population.

This percentage fluctuated in the range of a few percentage points in Ukraine. It is characteristic, that village teachers were behind all of the uprisings and rebel republics, such as Kholodny Yar.

It is impossible to win a war with no allies, with no support from Western community; when major countries aren’t even aware of your existence.

The US, German, English, French society and diplomats had very little knowledge of the Ukrainian issue. Their public thought relied on Russia’s opinion, and the latter was clearly anti-Ukrainian.

Western countries learned of Ukraine only during its war for independence. But it was too late.

Due to lasting activity of Polish and Czech émigrés, Poland and Czech Republic were considered counties who deserved independence. But very few people in the West understood what Ukraine was – even much later, after twenty years, before the start of the WWII.

However, we cannot say that the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917-1921 was a failure.

The Ukrainian Revolution set up the basis for new future state perspective. It became the point of no return for the independence movement, which led to reinstatement of the Ukrainian statehood in 1991.