Volodumyr Mursky — the UNR Government-in-exile representative in Istanbul

In 1932, with assistance from Volodymyr Mursky, the Agreement on Establishment of the Union State of Ukraine and Crimea was drafted and agreed upon by the UNR Government. The Agreement provided for mutual recognition of independence of the UNR and the Crimean People’s Republic and establishment of the common Union State upon defeat of the Bolshevik regime.

"…after the Battle of Poltava in 1709, Ukraine had been occupied by Moscow. Moscovites managed to crush the last of the Ukrainian forces. The Army was defeated, the Cossacks were at a loss, and the very country of Ukraine was renamed into Malorossiya. Ukrainian patriots had either been heading to Siberian labor camps, or forced to emigrate, forever leaving their Motherland.

Moscow’s oppression lasted for two centuries. It [Moscow] did everything in its powers to undermine the will of the Ukrainian people, but failed to obliterate it. And today, despite seeming political and economic ruin, despite Russia’s denial of not only Ukrainian national characteristics, but of the very fact of existence of Ukraine, Ukrainian people prove - they will not submit…"

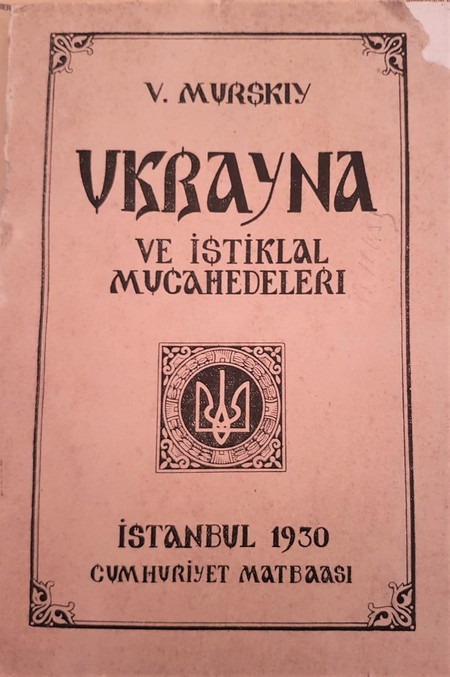

Volodymyr Mursky. Ukraine and its struggle for independence, 1930, Istanbul

The history of Ukrainian revolution, 100-year anniversary of which we are celebrating today, is not just a history of events. It is a history of figures, personalities, people whose immense energy, abilities and charisma served as drives to those events — shaped the destiny of both the people, and the state.

Volodymyr Vasyliovych Mursky is one of those patriots devoted to the idea of Ukrainian independence — public and political figure, writer, journalist, publicist, educator, diplomat, representative of the UNR Government-in-exile in Turkey, intelligence agent, and, in general, a multifaceted and talented person.

The year 2018 is 130th anniversary of his birth. One of the authors of this article had first come across Mursky’s name when he served as Consul at the Consulate General of Ukraine in Istanbul.

His attention caught a paper by Russian historian L. Sotskov "The unknown separatism. At the service of SD and Abwehr". The paper mentioned Volodymyr Mursky, calling him the representative of the UNR Government in Turkey in the 1930th. That’s what started the search for information on Volodymyr Mursky: biography details, burial place, and literary heritage.

In March 2018, through the efforts of stuff members of the Consulate General of Ukraine in Istanbul and activists of the local Ukrainian Cultural community, in particular, Alija Usenova, we finally managed to locate V. Mursky’s grave at the Feriköy Cemetery of Istanbul.

Volodymyr Mursky died 83 years ago, but there is still too little information about this person. Short biographical essays published in few encyclopedias and journalistic publications need to be expanded, or, sometimes, require substantial corrections.

|

| Volodymyr Mursky grave site at the Catholic cemetery of Istanbul, district of Feriköy. 2018, courtesy of Alija Usenova |

Volodymyr Mursky was born on November 10, 1888, in the Lviv suburb of Zamarstyniv. Volodymyr’s father, Vasyl Tymofiyovych Mursky, was very sick and died in young age, leaving behind four children (three sons and a daughter) who were raised by his wife Antonina Murska (Savko).

Antonina’s father was a priest, so the Murskys were good Christians. Volodymyr was the oldest of the four kids and the first to go to school. At the end of the 19th century, the family moved to Odesa, probably, to live with their relatives. There Volodymyr studied at the Richelieu Gymnasium — the most prestigious secondary school in the city.

Many of those who destined to become famous historic figures studied at the Gymnasium at the time; namely Horunzhi-General [the equivalent of modern Major General — translator note] of the UNR Army Andriy Gulyi-Gulenko. In 1905 the Murskys returned to Galicia, and Volodymyr completed his education in Lviv.

Among possible reasons for the family’s decision to leave Odesa might have been general instability in in the wake of the first Russian revolution. In spring strikes and political rallies started all over the city.

And in in June 1905, after rebel battleship Potemkin entered the port of Odesa, the government troops used weapons in a series of riots that broke out in the docks.

In October, mass murder of Jewish population (pogrom) took lives of over 400 people. Criminal situation in the city continued to deteriorate making it unsafe to stay in Odesa.

|

| Volodymyr Vasyliovych Mursky |

In Galicia Volodymyr Vasyliovych had completed his secondary education and pursued higher education in arts. He acquired profession of public educator.

We can assume, he graduated from Lviv University Philosophy Department, which was the only educational facility that trained teachers.

In that time, Galicia student scene was a favorable soil for building an individual national consciousness. Or, it was the education itself that shaped Volodymyr Mursky as Ukrainian patriot.

Upon graduating from university, starting 1914, Volodymyr Mursky worked as a public school teacher, was active member of Lviv "Prosvita" Society, and a member of "Vzayemna pomich ukrayinskogo vchytelstva" Society for mutual support of Ukrainian educators.

Mursky also regularly organized and took part in various events, concerts, choir performances hosted by the "Ukrainian club".

It is possible, that there at Lviv "Prosvita" society Volodymyr first met his future wife, Sofia Volska, who then was a Catholic gymnasium student just starting on a path of public activity.

The events of WWI forced Volodymyr Mursky to move back to Odesa, when the Western Ukraine became the scene of brutal confrontation between Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. Both armies included Ukrainian troops, while local population suffered repressions from both Austrian and Russian authorities.

In that time Odesa became a shelter to many refugees from Galicia and Bukovyna. Moreover, national revival and revolutionary events in the Dnieper Ukraine started earlier than in Ukrainian territories of Austro-Hungarian Empire, turning Odesa into kind of a magnet for nationally conscious Galician intellectuals.

Maybe, it was the news about the start of Ukrainian revolution that inspired Volodymyr Mursky’s return to the South Palmyra. It, probably, happened in early March of 1917.

During his second stay in Odesa Mursky emerged as public and political activist, one of the ideologists and leaders of Ukrainian national movement, who was closely involved in propaganda and educational activities. Probably, it was right here that he joined the Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party.

Almost immediately Volodymyr became a member of Odesa Ukrainian Leadership Committee ("Український керовничий комітет") — public organization that served as representative of the Ukrainian movement in the city and was acknowledged by both the Russian Provisional Government and the Ukrainian Central Council (Rada).

The organization was engaged in awareness-raising and educational activities. The Committee members took part in the all-Ukrainian National Congress held in Kyiv on April 6-8, 1917; also the Committee organized County Assembly in Kherson on June 29-30, 1917.

The Assembly adopted resolution by Volodymyr Mursky on using Ukrainian language in schools and churches, as well as the return of Ukrainian teachers and Galicia prisoners-of-war from Siberia labor camps.

Around that time Mursky was elected to the Finance Commission of Ukrainian Leadership Committee.

Ukrainian Leadership Committee began publishing weekly newspaper "Ukrayinske slovo" in Odesa, which propagated the idea of Ukrainian independence.

Together with the first Commissar of Odessa appointed by The Ukrainian Central Council (Rada), Volodymyr Mursky headed the newspaper’s editing committee and published seven of his own opinion pieces.

In May 1917 Mursky was elected a scribe of the Ukrainian Teachers Union, established by organizational assembly of the Ukrainian teachers of the region.

The Union’s objective was to develop national education in Odesa — as a counterbalance to the city’s Russian Teachers Union. At the Assembly V. Mursky gave a speech "On teachers’ organization and its activity".

In addition, in June 1917 V. Mursky was elected as a scribe of public organization "Komitet dopomogy vyselentsiam Galychyny, Bukovyny y Ugorshchyny" ("Committee for Assistance to Refugees from Galicia, Bukovyna and Hungary") that provided aid to Ukrainian refugees from Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Apart from public political activity, during his stay in Odesa, Volodymyr Mursky also perused teaching career. He taught Ukrainian language at training courses for railway stuff, postal workers and telegraph employees, and at the Odesa Military Academy; at Ukrainian Studies courses for teaching stuff Mursky gave lectures on Ukrainian language, literature, history of political struggle in Galicia, history of Ukrainian music. He also gave private violin lessons.

Mursky was at the peak of his creative powers: less than in half a year he wrote and published over 40 articles in Ukrainian newspapers of Odesa, compiled a collection of Ukrainian revolutionary songs that, unfortunately, have not yet been published.

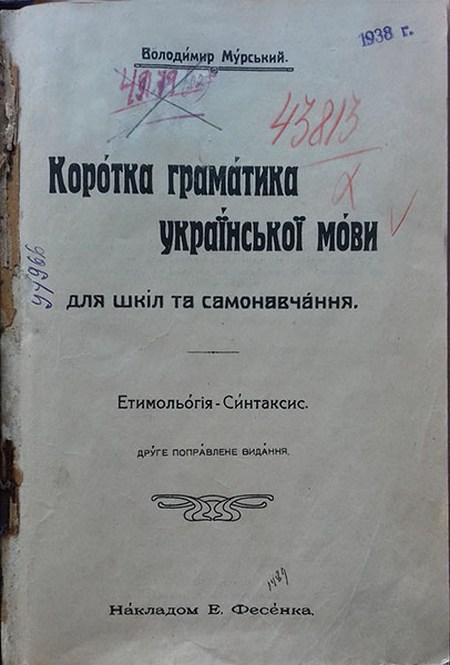

In 1918 Mursky’s textbook "Korotka gramatyka ukrayinskoyi movy dlia shkil ta samonavchannia" ("Short Ukrainian Grammar for Schools and Self-study") was published.

Some reviewers criticized the textbook for its orientation towards Galicia dialect of the Ukrainian language.

However, the local Ukrainian teacher’s union recognized this textbook as "one of the best" and recommended it "for teaching Ukrainian language in secondary schools".

Later, on April 4, 1918, the commission for developing Ukrainian language textbooks at the Publishing Department of the Ministry of Education of the UNR had chosen Ukrainian Grammar textbook by V. Mursky as the main textbook for teaching in the first and second grades of secondary and higher elementary schools.

|

| Textbook "Short Ukrainian Grammar for Schools and Self-study " by V. Mursky (1918) |

By the way, in 1929, when Volodymyr Mursky was in Istanbul, he asked the Secretary of the Ukrainian community in Turkey M. Zabjello to find a copy of that very textbook and send it to him with so called "travellers".

With the start of war between the UNR and the Soviet Russia Bolsheviks’ activity in Odesa intensified. In 1918 they seized power in Odesa using military means and established the Odessa Soviet Republic, which recognized the supremacy of the RSFSR.

Ukrainian military and most of Ukrainian political leaders left Odesa. However, Volodymyr Mursky had been unable to flee, and was arrested by Bolsheviks at the meeting of local "Prosvita" that was discussing military actions to counter Bolsheviks.

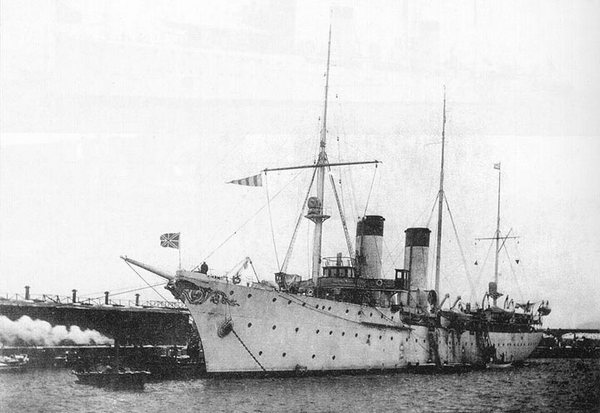

By the ruling of revolutionary tribunal Mursky was sent to Odessa prison, which saved his life. Despite horrible prison conditions, the prison didn’t practice torture, physical violence or murder, as it happened at the Bolshevik battleship "Almaz" where operated the so called Committee on combating counterrevolution.

The circumstances of Mursky’s release from prison remind of a spy thriller. As the UNR Army and allied Austro-German troops were approaching Odesa, the chief warden Vernygora on his own initiative released Mursky from prison, and even personally drove him home.

He left with an advice not to stay for a night. Mursky, under alias of engineer Schmidt, hid in one of the city’s sanatoriums until the return of the Ukrainians.

That night Bolshevik sailors searched his home and found explosives, that were planted there beforehand to provide grounds for re-arrest of Odesa national movement activist with the charges that would ensure his execution.

|

| Battleship "Almaz" |

Mursky was assigned to coordinate relations with Austrian-German headquarters on behalf of the Ukrainian authorities of Odesa (probably, due, in part, to his knowledge of German language), and elected Commissioner of Justice at Odesa Ukrainian City Council.

Still, Mursky’s activity remained focused on information and propaganda and cultural education.

From March to September 1918, in Odesa, together with M. Slabchenko, L. Brudny and V. Ponomarenko, he issued an independent social-democratic political newspaper "Vilne zhyttia" (Free Life).

In the newspaper Mursky published at least 16 articles under his own name and several dozen articles under alias "V.M." in. All of Mursky’s works were infused with idea of building independent democratic Ukrainian state, thus, with the establishment of Pavlo Skoropadsky regime they became a censorship target.

Volodymyr Mursky continued to work in close collaboration with local "Prosvita" organization, took part in opening its departments in different districts of Odesa, organized national choir, Taras Shevchenko Literature Fund, "crowdfunding" of the city’s Ukrainian affairs; initiated a protest against Russification policy, and much more.

Mursky’s second Odesa period ended on August 30, 1918, when Volodymyr left Odesa for Kyiv.

In the capital Mursky worked at democratic non-party daily newspapers "Vidrodzhennia" and "Trybuna" that published works of such famous statesmen and political and cultural activists as the Head of UNR Directory Symon Petliura; UNR Directory Minister if Interior O. Salikovsky, who acted as "Trybuna " editor in chief; one of the leaders of the Central Rada S. Yefremov; translator and journalist N. Surovtseva; journalists P. Hayenko, P. Pevny (co-editors of "Vidrodzhennia"), A. Khomyk; professor of Kyiv University O. Hrushevsky, and others.

In Kyiv V. Mursky continued his public activities; he kept in contact with S. Shelukhin, P. Stebnytsky, K. Losky, A. Yakovliv, D. Dontsov. The latter, in his memoirs, mentions September 12, 1918, meeting on issues of Ukrainian foreign policy that took place at Kyiv "Metropol" restaurant.

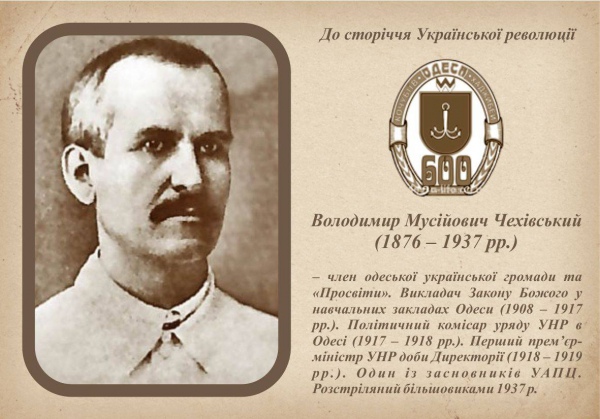

After the fall of Skoropadsky regime, the assertion of the Directory and reestablishment of the UNR, V. Mursky was co-opted as member of UNR delegation to a peace conference in Paris.

Perhaps it was, in part, due to Mursky’s personal acquaintance with Volodymyr Chekhivsky who, at the time, served both as the Head of UNR Council of Ministers, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Additional Mursky’s advantage was the knowledge of the second foreign language — French.

|

| Volodymyr Chekhivsky |

Mursky stayed in Vienna that became his first place of exile.

In Vienna, starting June 1919, together with renowned journalists and social activists V. Pisnachevsky, I. Kedryn and A. Khomyk, Mursky worked as editor and journalist for "Volia" magazine.

Mursky became friendly with V. Pisnachevsky — doctor, member of the USDP, journalist and publicist — during their common activities in Odesa in 1917—1918; and with A. Khomsky — when they worked together at "Vidrodzhennia" newspaper in Kyiv in 1918.

However, in the beginning of 1920, due to clash of opinions on change in magazine’s perspective, Mursky, together with Oleksandr Oles, stated a new magazine — "Na perelomi".

In 1920 Volodymyr Mursky was appointed Press Officer at UNR Embassy in Vienna. He continued to give lectures — to workers and prisoners-of-war — and took part in creating a Union of Ukrainian Journalists.

In September 1920, together with Serhiy Shelukhin, who was his friend since Odesa, Mursky moved to Poland.

In Tarnów, where the UNR Government-in-exile was stationed, Mursky fully committed himself to public political activity. He became a member of the UNR Council that performed functions of provisional parliament-in-exile.

He also joined editorial team of "Za derzhavnist" magazine published by the Ukrainian Military and History Society, established in 1920 in Warsaw by the UNR army veterans.

Upon signing of the Treaty of Riga that mandated the UNR Government to leave Polish territory, V. Mursky was forced to look for a job to provide for himself and his family.

He worked at a bank first in Torun, and later in Krakow.

He also mastered radio technology, popular in Europe in the beginning of 1920s. It became Mursky’s hobby, and a way to earn a living.

Mursky completed radio technology training in Krakow. When a radio station opened in the city, Mursky made several speeches regarding Ukrainian affairs.

V. Mursky had never stopped his public political activity. He worked at Krakow department of the Ukrainian Central Committee — Ukrainian émigrés’ public organization that carried out cultural and educational activities, provided legal and financial aid to Ukrainian émigrés in Poland.

Since the Government-in-exile was unable to perform any legal activity on the territory of Poland, the Ukrainian Central Committee worked in close cooperation with the latter and performed a function of public representative of sorts.

In February 1922 Volodymyr Mursky was appointed interim Director of the Press and Information Department with the UNR Ministry of Press and Propaganda.

He resumed publication and distribution of Ukrainian periodicals propagating Ukrainian independence among diaspora community, and on the territory of Bolshevik Ukraine.

Acted as adviser of the UNR Minister of Foreign Affairs. Was an active member of Promethean movement, aimed at uniting national independence movements of former Russian Empire and Bolshevik USSR and establishing independent states.

In January 1922 V. Mursky met Yuriy Tiutiunnyk in Lviv and delivered letters by Tiutiunnyk to the UNR Government.

As the archives of the Ukrainian Intelligence Service got declassified and the information was made public, it revealed certain biographical information about Volodymyr Mursky’s activity in Istanbul 1929 to 1935.

This is the last and the most eventful period of his life, that had great influence on the activity of Ukrainian community in Istanbul, as well as on all of the organized political Ukrainian émigrés in Turkey.

In the late 1920-s Istanbul became the center of Soviet intelligence network. It operated as headquarters for intelligence activities not only in Turkey, but in all of the Eastern Arabia.

In addition, Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) under SNK of the USSR conspired to use the Ukrainian community of Istanbul in special operation against the UNR exile leaders, aimed at identifying the UNR communication channels of illegal contact with secret supporters in Ukraine.

The operation was supposed to be deployed via Odesa by SPD Foreign Department ran by OGPU.

According to the archive, starting 1925, SPD USSR agency managed to recruit as agents several people, including secretary of Ukrainian community in Istanbul M. Zabjello.

They sent regular reports to Kharkiv Foreign Department of SPD USSR with the daily and sometimes hourly information on activity of the UNR representative in Istanbul.

The Soviet Intelligence infiltrated émigrés on such a deep level that they controlled almost all of the correspondence of the Ukrainian community in Istanbul with Warsaw and other European centers that sheltered UNR Government-in-exile.

So, when in April 1929 Volodymyr Mursky was appointed as Representative of UNR Government-in-exile in Turkey, he landed right in the center of "hornet’s nest" of the Soviet intelligence, and immediately became their target.

Interest to Mursky’s persona on the part of SPD was piqued by his patriotic and national views, prolific anti-Soviet activity and the fact, that apart from his direct diplomatic duties, he also performed some intelligence activity for the UNR Special Services.

|

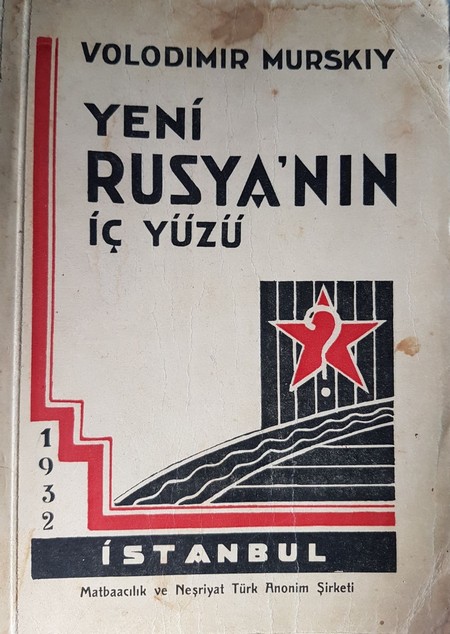

| Book "The Real Face of the New Russia" by Volodymyr Mursky |

Volodymyr Mursky lived and worked in Istanbul. His responsibilities included resolving issues of Ukrainian diaspora, serving a liaison with the Turkish authorities, representatives of foreign diplomatic and special services, collecting intelligence information on events in Ukraine.

Mursky also arranged sea delivery of printed pro-Ukrainian propaganda materials to the Ukrainian ports, especially Odesa.

Volodymyr Mursky established good working relations with Ecumenical Patriarch Photios II. In 1930, with Mursky’s organizational support, the Chairman of the UNR Council of Ministers-in-exile Vyacheslav Prokopovych visited Istanbul, and had a meeting with Photios II where he raised the issue of Tomos on autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

V. Mursky also maintained close relations with the leaders of Crimean Tatar diaspora in Turkey, in particular with Cafer Seydamet (Qirimer).

In 1932, with assistance from Volodymyr Mursky, the Agreement on Establishment of the Union State of Ukraine and Crimea was drafted and agreed upon by the UNR Government.

The Agreement provided for mutual recognition of independence of the UNR and the Crimean People’s Republic and establishment of the common Union State upon defeat of the Bolshevik regime.

Volodymyr Mursky published two books in Turkish language: "Ukraine and its Struggle for Independence" (1930) and "The Real Face of the New Russia" (1932) where he actively promoted the need to reinstate independent Ukraine and destruction of Bolshevik regime.

Mursky presented the first book to the President of the Republic of Turkey Mustafa Kemal, and receive glowing reviews in the Turkish and Azerbaijan emigrant press. The second book was delivered to Turkish military leaders, political and cultural activists.

|

| Book "Ukraine and its Struggle for Independence" by V. Mursky |

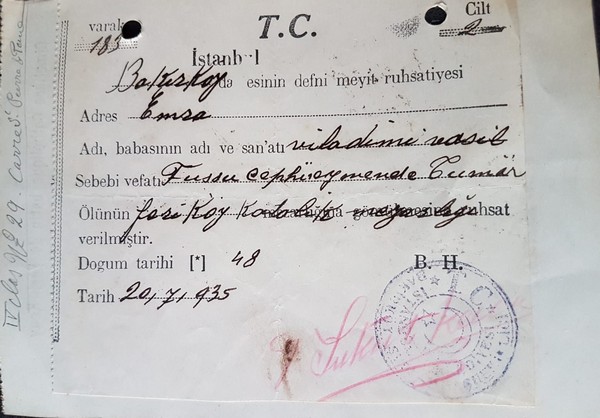

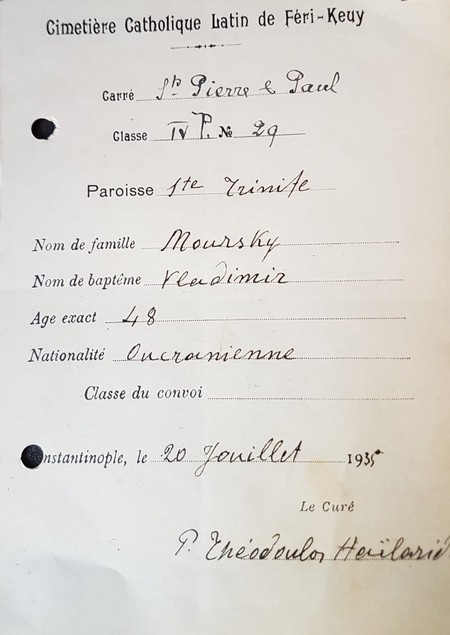

Volodymyr Mursky died at the age of 47, on July 19, 1935. Craniotomy performed by specialists of Bakırköy District Hospital determined Mursky’s untimely death to be caused by a brain tumor.

Long-term stress, constant sleep deficit and hereditary factors might have caused the disease. However, we should not neglect the possibility that Soviet Special Service methods of eliminating political opponents might have been involved.

In accordance with the wishes of Volodymyr Mursky’s wife, he was buried at the Catholic Cemetery in Istanbul. Funeral took place on July 20, 1935, and was attended by North-Caucasian, Azerbaijan, Turkmen and Georgian émigrés of Istanbul.

The casket was covered by the national flag of Ukraine and decorated with Ukrainian ribbons. The UNR had never appointed another representative to Istanbul after the death of Volodymyr Mursky.

|

|

Volodymyr Mursky’s certificate of burial (in Turkish language). Photo: A. Usenova |

Volodymyr Mursky’s wife Sofia (Zosia) Volsko-Murska (1894–1946) was a public activist, English and German translator, and a philologist.

She was born in Kaniv region in 1984, studied at Catholic School with St. Onufri monastery in Lviv (the Bernardine Church and Monastery). Later, she studied in France and England.

In 1918, on Vyacheslav Lypynsky recommendation, she was appointed translator to the UNR Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1920, Sofia, as a member of the Ministry, was forced to emigrate.

She was a secretary and one of the leaders of the Ukrainian Woman’s Society created in Vienna on June 18, 1920. She married Volodymyr Mursky in 1921 in Vienna. Sofia Volsko-Murska was the first to translate the play "Babilin exit" by Lesia Ukrainka into English language.

The play was published in the Great Britain and the USA in 1916. Sofia was friends with Oksana Dragomanova — Lesia Ukrainka’s cousin and a niece of famous historian Mykhailo Dragomanov.

|

|

Volodymyr Mursky’s certificate of burial in French, issued by the Catholic cemetery. Photo: A. Usenova |

The latter was also famous among the Ukrainian creative intellectuals of the end of the 18th the beginning of the 19th century.

During her stay in Turkey, Sofia Volsko-Murska was engaged in public activity. She took part in the international Woman’s Congress held in Istanbul in 1935. In 1936, upon the death of her husband, S. Volsko-Murska, with her children, moved to Galicia; and at the end of WWII the family moved to Germany.

As a widow of the UNR official S. Volsko-Murska received financial assistance from the UNR State center-in-exile, which was in turn financed by the Government of Poland. She died 1946 and was buried in Munich at the same cemetery as Stepan Bandera.

Mursky’s daughter — Sofia Murska (1921—1995) — was born in Tarnów (Poland). In the late 1920-s she studied at a secondary school in Paris, where she stayed with her mother’s cousin Tarnów Maria Stephanivna Pchelynska.

After the Murskys moved to Istanbul, in autumn 1930, Sofia was transferred to the local French gymnasium. Since she was underage, her aunt accompanied Sofia to her parents. Later, M. Pchelynska also came to stay with the Murskys and became an active member of Ukrainian community in Istanbul.

Upon the death of her father, Sofia moved to the Western Ukraine with her mother. On August 5, 1942, she married Turkology scholar Yevgen Zavalynsky, who was famous in Galicia, and, later, in all of the Ukrainian diaspora.

They were married in Lviv in St. Onuphrius Church at the monastery, where Sofia’s mother used to go to school. Sofia Murska (Zavalynska) spoke French and Turkish. At 18 she published popular essays about Turkey in various Lviv newspapers.

After she got married, Sofia and her husband both worked as teachers in the village of Dubanevychi, near Lviv (Gorodok raion, Lviv Oblast).

January 18, 1944, Zavalynskys had a son, named Volodymyr, probably after his Grandfather. Later that year the family immigrated to France; in 1950 Zavalynskys moved to Australia and settled in one of Melbourne neighborhoods.

Sofia Zavalynska and her husband were public activists. Sofia worked as a teacher at Ukrainian school, was a secretary of the School Council, and performed other duties as a member of the Ukrainian community in Melbourne.

She also mastered craft of pysanka (decorated egg created by the written-wax batik method with traditional folk motifs — translator’s note), and published essays on Ukrainian art.

Yevhen and Volodymyr Zavalynskys regularly published in the Shevchenko Society publications in Australia.

|

| V. Mursky’s grave at the Catholic cemetery of Istanbul, district of Feriköy Photo: A. Usenova |

Her husband, Mykhailo Makarovych Suprun was born in town of Vorozhba, Sumy Oblast, in 1923. His family suffered severely during the Holodomor of 1932—1933. These events are described in the memoirs of Suprun M. M., published under the title: "Golgofa ukrayinskogo narodu" ("The Calvary Golgotha of the Ukrainian People").

Volodymyr Mursky’s mother, Antonina, stayed in Lviv and survived both Soviet and Nazi occupation. In 1944 together with the family of her daughter, Ivanna Petriv, moved first to Germany, and later to Belgium, where she took active part in life of the Ukrainian community. She died shortly after the end of WWII and was buried in Brussels.

Mursky’s sister Ivanna-Khrystyna Murska (Petriv) (20.01.1892 — 5.11.1971), inspired by the example of her older brother went down in history of both Ukraine and Ukrainian independence movement as an activist, a teacher and a writer.

She moved to Belgium with her mother, and later immigrated to Canada, where she became prominent figure among Ukrainian émigrés. Her life and work is described in the previously paper of I. Stazhnikova.

Mursky’s nephews on his sister’s side Yaroslav-Volodymyr (born 1915), Rostyslav-Denys (born 1923) and Mykola (born 1925) Petrives served at the Waffen SS 1st Galician Grenadier Division in the WWII.

The youngest got captured by the Soviet troops and was sentenced to Siberian prison camps, the others were captured by the allies. The oldest — Yaroslav-Volodymyr —immigrated to Canada, and was later joined by his mother, V. Mursky’s sister Ivanna-Khrestyna Petriv.

Volodymyr’s brother, Petro Mursky (born 1894) became a renowned Lviv cultural figure and educator, directed plays by Ukrainian playwrights, and was active supporter of the Ukrainian amateur theater in Galicia. He also authored a number of plays and performances.

The youngest brother — Levko (born 1897) had died in the WWI.

Volodymyr Mursky lived a short, but very eventful life — the life of a tireless fighter for independence of his people. Till his very last breath he believed that his dream — the demise of the Socialist empire and reinstatement of independent Ukrainian State — will come true.

Though it happened 56 years after his death, his merit to the cause is undeniable.

Р.S.: Unfortunately, the authors of this article were unable to determine biographic detail for all of the Volodymyr Mursky’s family. In particular, the information regarding the second Mursky’s daughter Olena is incomplete.

The fate of Petro Mursky also remains unknown. The process of collecting such information is extremely complicated, so we would be thankful to anyone who could be of assistance in this matter. Contact address: dmit.kozlov@gmail.com.